A member of the Federal Reserve Board is complaining that too many of the new jobs created since the recovery began are low-wage, part-time, temporary, or all three.

Speaking last week at a conference in Washington, D.C., Fed Governor Sarah Raskin said, “Flexible and part-time arrangements can present great opportunities to some workers, but the substantial increase in part-time workers does raise a number of concerns.” These include, she said, a lack of benefits, lower pay rates, and, often, no sick or personal days off.

Two-thirds of the jobs lost in the recession, she said, “were in moderate-wage occupations, such as manufacturing, skilled construction, and office administration jobs.” But fewer than a quarter have come back. “Recent job gains,” she observed, “have been largely concentrated in lower-wage occupations such as retail sales, food preparation, manual labor, home health care, and customer service.”

Furthermore, Raskin said, employers are increasingly turning to temporary — “contingent” — workers because of the flexibility they offer. During the recession, 10% of the jobs lost were temp. However, 25% of the jobs created since the recovery began have been temp.

Furthermore, Raskin said, employers are increasingly turning to temporary — “contingent” — workers because of the flexibility they offer. During the recession, 10% of the jobs lost were temp. However, 25% of the jobs created since the recovery began have been temp.

“The flexibility may be beneficial for workers who want or need time to address their family needs,” Raskin acknowledged. “However, workers in these jobs often receive less pay and fewer benefits than traditional full-time or permanent workers, are much less likely to benefit from the protections of labor and employment laws, and often have no real pathway to upward mobility in the workplace.”

Although not blaming any single factor — except for the overall job loss during the recession — Raskin said that the trend toward lower paying and temp work as well as stagnant wages for those who held on to their jobs, has pushed up the poverty level in the U.S.

“The poverty rate has risen sharply since the onset of the recession, after a decade of relative stability, and it now stands at 15 percent — significantly higher than the average over the past three decades,” she said.

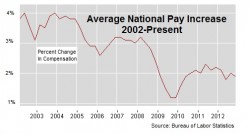

Economists have raised the alarm about the quality of the jobs being created, citing similar statistics, including wage data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, showing, on average, that pay increases have, on average nationally, gone from over 3.5% annually a decade ago to under 2% last year.

That the issue is now being addressed by the Federal Reserve suggests the nation’s banking managers may be growing concerned about the imbalance and what it may mean for the continuing recovery.

Said Raskin:

Wage growth has remained more muted than is typical during an economic recovery. To some extent, the rebound is being driven by the low-paying nature of the jobs that have been created. The slow rebound also reflects the severe nature of the crisis, as the slow wage growth especially affects those workers who have become recently re-employed following long spells of unemployment. In fact, while average wages have continued to increase steadily for persons who have remained employed all along, the average wage for new hires have actually declined since 2010.

Despite the concern, there’s not much the Federal Reserve can do to change the situation. As Raskin noted, “While the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy tools can be effective in promoting stronger economic recovery and job gains, they have little effect on the types of jobs that are created, particularly over the longer term.”